↧

Frida Returns

↧

Feuillevert: Green Leaves And The Dream Of A Common Language

“I was beginning to speak of the famous poets I knew when Garfield stopped me with ‘Just a minute!’ He ran down into the grassy space, first to one fence and then to the other at the sides, and waved a wild arm of invitation to the neighbors….’Come over here!’ he shouted. ‘He’s telling about Holmes, and Longfellow, and Lowell, and Whittier!’ and at his bidding forms began to mount the fences and follow him up to his veranda. ‘Now go on!’ he called to me, when we were all seated, and I went on, while the whippoorwills whirred and whistled round, and the hours drew toward midnight.” - William Dean Howells, from Years Of My Youth (1916)

As many times as I have read this paragraph, it never fails to catch at my throat. American poets in the 19th century,including those referenced above (Oliver Wendell Holmes [1809-1894], Henry Wadsworth Longfellow [1807-1882], James Russell Lowell [1819-1891] and John Greenleaf Whittier [1807-1892] ) had an intimate relationship with their readers' lives, without benefit of radio, television, or the internet. Their works were taught in schools, memorized for pleasure and education, and presented at public occasions of all sorts, from family gatherings to patriotic holidays.

"(T)o try to figure out what the poem means, as much as what the poem means in our lives" is how Joan Shelley Rubin describes what has changed in how we read poetry today. Rubin says that our reading has become less personal. That may be why this story of poets on a summer night seems like a dream.

William Dean Howells (1837-1920) had become an assistant editor of the Atlantic Monthly in Boston, just years earlier by one of the magazine's founders, John Greenleaf Whittier. Howells would become a respected novelist, with the publication of Their Wedding Journey in 1872.

"(T)o try to figure out what the poem means, as much as what the poem means in our lives" is how Joan Shelley Rubin describes what has changed in how we read poetry today. Rubin says that our reading has become less personal. That may be why this story of poets on a summer night seems like a dream.

Howells, as editor of Harper’s, wrote for the magazine in March of 1902 about the importance of “that great reading world with which the small writing world is really so little in touch.”

I want to borrow an idea from another poet, the much-missed Adrienne Rich (1929-2012) who described Beethoven's music as "music without the ghost of another person in it" to describe the self-examining world of our contemporary poets. In the summer of 1870, James A, Garfield (1831-1881) was almost half way through his eighteen years as a member of Congress. Garfield would be elected as the 20thPresident of the United States in 1880 but, in the event, he served in office for only 200 days; assassinated on September 19, 1881.

Garfield was raised on an Ohio farm by his widowed mother. The family had little money, so the young Garfield worked at a series of jobs to earn enough to attend Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, After graduating in 1856, he moved back to Hiram where he became the president of Western Reserve Eclectic Institute.William Dean Howells (1837-1920) had become an assistant editor of the Atlantic Monthly in Boston, just years earlier by one of the magazine's founders, John Greenleaf Whittier. Howells would become a respected novelist, with the publication of Their Wedding Journey in 1872.

Whittier, the poet whose middle name Greenleaf derives from the French word feuillevert (green leaf) was color blind. He grew up on a a farm in Haverhill, Massachusetts as part of a large and extended family. Descended from Huguenot immigrants, the American Whittiers became Quakers and, not surprisingly fro their time, supporters of the anti-abolitionist movement. Whittier's first poem was published without his knowledge when his sister sent it to William Lloyd Garrison at the Newburyport Free Press in 1824. Whittier had little education but, with encouragement from Garrison, he earned money as a shoemaker that helped pay his tuition at the Haverhill Academy. In his works Whittier's great themes were compassion and social responsibility. Today, a bridge over the Merrimack River that connects Newburyport to Amesbury, where Whitter is buried, bears his name.

To read more:

1.Years Of My Youth by William Dean Howells was originally published in 1916 by Harper & Brother of New York and reprinted most recently by Indian University Press at Bloomington in 1975.

2. Songs of Ourselves:the uses of poetry in Americaby Joan Shelley Rubin, Cambridge, Belknap Press, Harvard University: 2007.

3. John Greenleaf Whittier: A Biographyby Roland H. Woodwell, Haverhill, Trustees of the John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead: 1985.Image;

1. unidentified photographer - The James & Lucretia Garfield home, 6825 Hinsdale Street, Hiram, Ohio, Ohio historical Society, Columbus.

1. unidentified photographer - The James & Lucretia Garfield home, 6825 Hinsdale Street, Hiram, Ohio, Ohio historical Society, Columbus.

↧

↧

Cote d'Azure: This Too Was The Summer Of 1914

In the summer of 1914 Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923) was eighty-one years old. In his long career as an engineer and architect he had experienced monumental successes (the Garabit Viaduct in the Massif Central [1882] and the Eiffel Tower without which Paris would not be Paris [1889]) and a humiliating defeat in the long drawn out scandal that was the French Panama Canal Company. Although Eiffel had just engineered the first wind tunnel in Paris on Rue Boileau in 1912, he devoted his later years mostly to more theoretical projects.

Eiffel had been born on the Cote d'Azur and he returned there in 1896, settling at Beaulieur-sur-Mer, a coastal Mediterranean village near Nice and Monte Carlo. A widower since the death of his beloved wife Marie Guadelet, Eiffel lived at Villa Durandy (photograph at left) where he was often visited by his five children. Indeed, his daughter Claire lived nearby at Villa Salles with her husband Georges.

Eiffel had been born on the Cote d'Azur and he returned there in 1896, settling at Beaulieur-sur-Mer, a coastal Mediterranean village near Nice and Monte Carlo. A widower since the death of his beloved wife Marie Guadelet, Eiffel lived at Villa Durandy (photograph at left) where he was often visited by his five children. Indeed, his daughter Claire lived nearby at Villa Salles with her husband Georges. Georges Salles (1889-1966) was a French art historian who made important archeological excavations in Iran, Afghanistan, and China. In 1926, Salles would join the Musée du Louvre, where he became curator of Asian Art and helped to organize the first exposition of Byzantine art in 1931. Ten years later, Salles became the director of the Musee Guimet. While there, he joined in the French resistance to the Nazi occupation of France during World War II. Salles was later credited by art historian Kenneth Clark with saving many works of art from looting or destruction in wartime. Both Picasso and Matisse painted his portrait.

But that was all in the future in the summer of 1914. The Salles were a young married couple, enjoying a summer idyll by the sea. Many of those who lived through that summer later averred that the weather was perfect and, looking at these pictures of summer at Villa Salles, who would dare to argue? Fixed forever (or as close one can get using the unstable grains of starch employed in autochrome photography) the Cote d'Azur has never appeared more heavenly. Eiffel, Claire, Ninette Salles, and Georges captured together at the click of a shutter. Did they have any inkling of the frantic diplomacy taking place in the capitals of Europe? Too much testimony as to the impossibility of war has been given for us to think that Georges Salles had any idea that he would return from battle four years later as the recipient two times of the Croix de guerre. For the time being the elegant double-masted schooner was not a ship of war.

The allee of the palm trees.

Ninette in the Japanese garden.

Images:

All are by "unidentified photographer", autochromes from the collection of the Musee d'Orsay, Paris.

↧

Sir Philip Sidney: A Sonnet

Sonnet XXXI

"With how sad steps, O Moone, thou climb'st the skies!

How silently, and with how wanne a face!

What, may it be that even in heavenly place

That busy archer his sharpe arrowes tries?

Sure, if that long-with-Love-acquainted eyes

Can judge of love, thou feel'st a Lover's case;

I read it in thy lookes; thy languisht grace

To me that feele the like, thy state descries.

Then, even of fellowship, O Moone, tell me,

Is constant Love deem'd there but want of wit?

Are beauties there as proud as here they be?

Do they above love to be lov'd, and yet

Those Lovers scorn whom that Love doth possesse?

Do they call vertue there, ungratefulnesse?"

- Sir Philip Sidney

Of all poems, the sonnet should be read and treasured and widely available. The word comes from Old Provencal (sonet) by way of Italian (sonetto) and it is a little poem or song. But in a misplaced zeal to clear the shelves of unnecessary volumes, libraries are selling off insufficiently circulated items on the theory that they have lost their value to readers who may not even know of their existence because they are unfashionable. I was searching for George Meredith's 50-sonnet sequence Modern Love, a book I had borrowed several times but not recently enough, only to find that it was gone. Originally published in 1862, Meredith, an English poet and novelist, detailed the disintegration of his his marriage to Mary Ellen Peacock, daughter of poet Thomas Love Peacock, and his distress when she left him for another man. I consoled myself with another old favorite, Astrophel and Stella (Starlover and Stars), written during the 1580s by the Elizabethan poet Sir Philip Sidney (1554-1586).

Astrophel and Stella (Starlover and Star), published in 1591, was the first great Elizabethan sonnet sequence, second only to Shakespeare's. In it, through self-revelation, Sidney ripped the mask off the Petrarch-ian sonnet. He had not intended his sonnets to be published so that may explain their intimate tone. Fortunately for us, his friends saved them from oblivion, publishing the sonnets after his death. Henri Etienne called Sidney vir generosus, 'a man ‘in all ways generous.’ (Geneva: 1576) and his works is that, too. Unusually for a child of noble privilege Sidney took generous care of the people who worked for him, even giving money to a blind harpist at the tender age of eleven.

The self that Sidney revealed is his poetry is conflicted and inspired by what Robert Browning described in Joocoseria (1883) as “Never the time and the place./ And the loved one all together.”

Philip Sidney had known Penelope Deveraux since childhood. So it was not unusual that Penelope was eventually suggested as a bride for for the young man but in the Elizabethan fashion, wealth and rank outweighed mutual attraction on the marriage scales. Penelope’s marriage in 1582 turned out to be an unhappy one, Her husband, Lord Rich, treated her cruelly and, after Sidney’s death, Penelope was able to obtain a divorce. The poet’s friends averred that she had loved him. Sidney though,had apparently dithered about courting her , only to suffer the sharp sting of regret after she married someone else; the experience was more than a poetic conceit to him. Under the guise of a lovelorn shepherd Sidney felt free to express his melancholy and sexual frustration.

Sonnet XXXI is unforgettable from its first line, alhtough verging on the ungrammatical ("With how sad steps"), a strange and riveting ode to the moon. Sidney who claimed in his Defence of Poesy that "The poet nothing affirmeth and therefore never lieth," is also a turner of tables, ultimately by suggesting darkly that those who receive love without returning it are ungrateful rather than virtuous.

These poets and also St. Bonaventure, whose Itinerarium mentis in Deum of 1259 contains the following sentiment, are our familiars. Their poems may sound slightly strange to our 21st century but they belong to us.

"But if we regard speech with a view to its aim, it serves to express, to teach, and to move. But it always expresses something by means of an image, it teaches by means of a force of light."

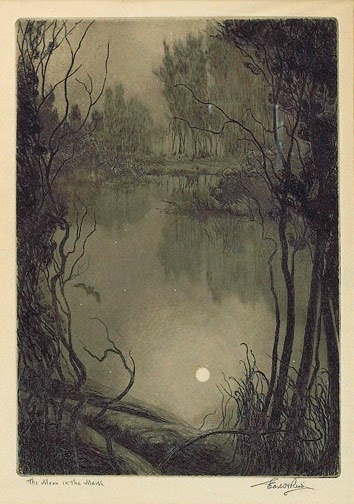

Image:

Earl Reed (1863-1931) - The Moon in the Marsh, undated, Art Institute of Chicago.

↧

Arthur Bowen Davies: An Artist From Utica

"Modern art owes more to him than anyone else." - Walter Pach, January 14, 1958, MWP Institute Archives.

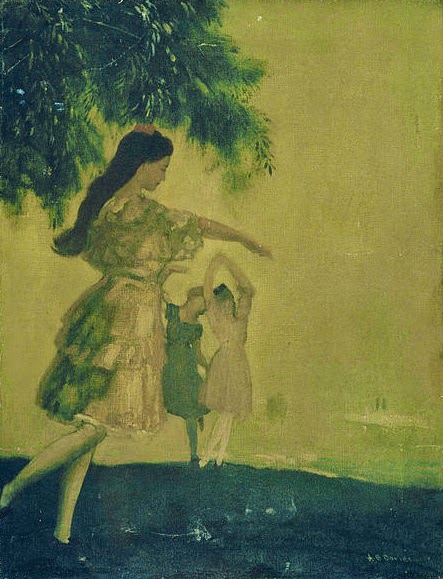

Idealized nudes at play in antique landscapes. That is all most museum-goers know of Arthur Bowen Davies after seeing his most famous painting Unicorns or Legend – Sea Calm(1906) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Not inaccurate so far as it goes but there is more to Davies than that. His name is found most often these days in footnotes but his fingerprints are everywhere, especially in New York. He was, in fact, the principal organizer of the Armory Show in 1913, the exhibition that introduced modernism as a force to be reckoned with in the American art world. If you think you see a response to Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 (1912), the most notorious single piece of art from the Armory Show, in Figures (at left)

Arthur Bowen Davies (1863-1928), was born in Utica, New York, a city on the Mohawk River near the southern edge of the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York. One of several cities that grew up along the Erie Canal, Utica prospered with the growing textile industry. Three of its wealthiest families were also discerning and eclectic art collectors and their names are memorialized today in a museum and art school – the Munson Williams Proctor Institute, founded in 1919. A large touring exhibition of landscape paintings that visited the Utica Art Association in 1878 and included works by George Inness turned Davies’ interest in drawing into a vocation.

The bouillabaisse of Greek, Roman, and Renaissance, influences that went into his personal symbolism makes hash of standard art historical explication. Davies was equally as able to admire the tonialist meadow-scapes of Montclair, New Jersey by Goegre Inness and the symbol-laden places imagined by the Swiss artist Arnold Bocklin. In History of American Painting (New York, The Macmillan Company: 1927), Samuel Isham lauded Davies as the creator a unique mythic world. “It all has a naiveness, a belief in its own imaginings which recall early Florentine workers, the painters of allegories and decorators of cassone.”

Duncam Phillips, founder of the eponymously named Phillips Collection in Washington D.C.,, thought so highly of Davies that he commissioned a book his work in 1924 that included essays by some of the leading critics of the day, including Royal Cortissoz, Edward Walees Root, and Frank Jewett Mather, Jr: who wrote: “One likes to imagine some analogy with the accented and unaccented notes of a bar of music. Overt musical suggestion there is none. The figures are without function or evident relation, but they . are sufficiently bound together by a common sense of a quiet eagerness and expectancy. They live in a purely mental world. They may be conceived more literally as waiting for the first chord of a music in which they are to join.”

Davies was eclectic, if not omnivorous in his tastes. The man whose work was compared to the romantic Puvis de Chavannes was also the collector of Joseph Stella and Paul Cezanne. It was Davies whose advice guided Lillie Bliss and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller as they assembled their collections that became the foundation of the Museum of Modern Art.

Davies excelled at pastel. The British humor magazine Punch had dubbed James McNeill Whistler the “Genius of Smudge” in 1877 for his atmospheric use of pastel, not intending it as a compliment. A smudge is a technique used by artists in pastel and watercolor. Sadakichi Hartmann, writing as Sydney Allan in Camera Work 7 (July 1904) in “The Technique of Mystery and Blurred Effects”, argued that while the old masters would have considered modern artists like Davies limited, it was exactly this deliberate limitation that made them superior: “in the depiction of atmospheric effects and subtler emotion.” Arthur Bowen Davies left off dating or identifying his pastels, another form of smudging. To a farmer a smudge is a mass of burning organic matter, placed on the windward side of vegetation to protect crops from frost on cold nights. This too is a type of filter.

Davies is known to have favored working from the background forward in his landscapes, providing the opportunity to layer memories onto the scene in front of him. That is to say that Davies created his alndscapes in much the way that we look at them ourselves. If art criticism were no not skewed toward theories and away from observation at this particular moment, that would be so obvious as to be unremarkable. To my eyes the Davies landscape pastels are always filtered through a palimpsest of upstate New York, even when the subject is France, Italy, or Switzerland.

But the smudge and the palimpsest are techniques that resonated with something in Davies’ character as well as his work. It was only after his sudden death while vacationing in Florence that friends learned that Davies had maintained two wives and two families at the same time, a secret he kept for decades.

Images:

1. Arthur Bowen Davies - Figures, c-1914-16, Munson-Williams-Proctor Art Institute, Utica.

2. Arthur Bowen Davies - Park - possibly at Blois, France, c.1924, Munson-Williams-Proctor Art Institute, Utica.

3. Arthur Bowen Davies - the Dancers, no date given, Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

4. Arthur Bowen Davies - Chateau Langeais - Touraine, c. 1924, Princeton University Art Museum, NJ.

5. Arthur Bowen Davies - Mountain Moonlight, no date given, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

2. Arthur Bowen Davies - Park - possibly at Blois, France, c.1924, Munson-Williams-Proctor Art Institute, Utica.

3. Arthur Bowen Davies - the Dancers, no date given, Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

4. Arthur Bowen Davies - Chateau Langeais - Touraine, c. 1924, Princeton University Art Museum, NJ.

5. Arthur Bowen Davies - Mountain Moonlight, no date given, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

↧

↧

Tremble

↧

Emily Dickinson: A Private Spriit

"The difference between Despair

And Fear – is like the One

Between the instant of a Wreck –

And when the Wreck has been –

The Mind is smooth – no motion –

Contented as the Eyes

Upon the Forehead of a Bust –

That knows – it cannot see. -"

- a poem by Emily Dickinson, sometimes given the title The Difference

Dickinson knew what she called her ‘waylaying Light’ was unwelcome to organized religion, alarming to the pious. “When Jesus tells us about his father, we distrust him. When he shows us his Home, we turn away, but when he confides to us that he is ‘acquainted with Grief,’ we listen, for that is also an Acquaintance of our own.” This from one who defined herself as wicked while still a girl; she knew herself to be bold and incorrigibly open hearted. To this day, people fret over whether Dickinson was religious, even whether she was a moral person. Her ideas were, and still are, radical. Those dashes, so characteristic of Dickinson's work, are like signposts that point toward the future. Like the tides, never static. And now we are able to read her poems as written by her own hand.

For further reading: The Gorgeous Nothings, a facsimile edition of her manuscripts by Emily Dickinson, New York, New Directions: 2013.

Image:

Beatrice S.Levy - The Derelict, 1914, Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.

↧

Mark Rothko & Gregory Orr: From Desolation To Joy

"To be alive. Not just

The carcass, but the spark."

- Gregory Orr

Without some knowledge of joy, there would be no poignancy to desolation. This is mirror to the philosophical point that without some experience of injustice there would be no reason to invent the concept of justice. The This untitled painting from the Phillips Collection by Armenian émigré artist Mark Rothko (1903-1970) may surprise you but it is a painting where the luminous aspect of Rothko's work is undeniable. Although the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas is better known, the first gallery devoted to the artist was the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. Designed by Duncan Phillips himself in 1960, specifically to display four of Mark Rothko's paintings that he had purchased recently, the room was described by Rothko as a kind of "chapel."

“ With their embrace

They chose

Each other,

Which is

To choose death

And all that comes

Before it:

Sufferings

And joys

And infinite

Unintended harms.

Large choice

For such small arms.”

- To Embrace (from Eden and After)

For Gregory Orr, lyric poetry is “a means of helping individuals survive the existential crises represented by circumstances such as poverty, suffering, pain, illness, violence, or loss of a loved one." Here, Orr refers to the tragedy of his childhood: that he was the accidental instrument of his brother’s death, from, Burning the Empty Nests (1973) to his latest collection River Inside the River (2013).

The book contains three related sections, beginning with a version of the creation myth from Genesis "Eden and After". His Eden is static and eventless, a place to escape from, his Adam and Eve long to speak, to sing, to embrace language and each other.

Second is "The City of Poetry", where Orr names the poets in whose work he has found refuge in times of trouble, inviting readers to join with Sappho, Dickinson and Neruda.

Murder and thief

If half the rumors are true.

My best guess is that he wrote

“Ou sont les neiges d’antan” –

“Where are the snows

Of yesteryear” – a refrain

That followed a list

Of famous beauties he once knew.

I don’t claim he was the first

To lament that bodily beauty

Vanishes like melting snow,

But when you think of the city,

Remember Villon.”

In the penultimate sectionof River Inside The River, Orr with disarming clarity writes, "I'm an old man / Made young again / By the poems I love". We have the capacity, whether we exercise it or not, to redeem tragedy through art.

Orr writes in short stanzas, making music out of the surrounding silence (visible as space on the page). He distills language into emotion, as Rothko distilled emotion into paint.

Around a summer oak,

Words crowd around

The beloved –

Respectful, yet eager.

They sense her infinite

Possibility; they’re drawn

To his heart, large as a star.

Only some will be summoned,

Only some will be sung.” - excerpt from the final section of River Inside the River

In 1951, Wallace Stevens said “ in an age in which disbelief is so profoundly prevalent or, if not disbelief, indifference to questions of belief, poetry and painting and the arts in general are, in their measure, a compensation for what we have lost.”

Mark Rothko had said something similar already, in 1947, “Without monsters and gods, art cannot enact our drama: art’s most profound moments express this frustration.”

For further reading: River Inside the River by Gregory Orr, New York, W.W. Norton: 2013.

Image: Mark Rothko - untitled, 1968, Phillips Collection, Washington,D.C.

↧

A Map Of The Affections

"..It's something that everybody needs.." - Lowman Pauling & Ralph Bass.

If only there were a reliable map to affairs of the heart, its cartographer would become wealthy and rightly so.

The road to love begins, according to Madeleine de Scudery, at the city of Nouvelle amitié or New Friendship (at the bottom of the map). There are three tributaries to the River of Love which flows up the map’s center; respect, esteem, and affection. Along the Inclination River, are various way stations such as Fresh Eyes, Love Letter, Big Heart, and Generosity. On the opposite shore, Complacence, Little Care, Attendance, and Obeisance, offer alternatives of passion and virtue.

Marriage was not included in Scudery’s cartography, doubtless, because she saw emancipation from matrimony as the only freedom available for women in her time. She not only chose not to marry but managed to free herself from the burdensome guardianship of her brother Georges. Madeleine had been forced to leave her beloved Paris for three years from 1644-47 when Georges was appointed the governor of the Fort of Notre-Dame -de-la-Garde in Marseilles. In keeping with this view, at the top of the map is the terre inconnu of the Perilous Sea., deviating from New Friendship cab lead a woman to only bring a woman to Indiscretion, Perfidy, and Wickedness.

Madeline de Scudéry (1607–1701) created this Carte du tendre, a map of love, as a game to amuse her Parisian friends. Her salon, the Société du samedi (Saturday Society) held at her home in the rue de Beauce was attended The map rpoved so popular that Scudery incorporated it in the first volume of her novel Clélie, histoire romaine, published in 1654. Caught between the Sea of Enmity and the Lake of Indifference, it is no wonder that a woman might feel trapped between Scylla and Charybdis. Another unpleasant watery fate.

In the Paris of Scudery’s day, women were attempting to become accepted as authors in the (male) literary world. The Precieuses, as these women were called, were ridiculed by men, notably by Moliere in his very first play Les precieuses ridicules (1659). It was hardly a model of subtlety. As if that were not enough to banish the women, Moliere took another poke at them in 1672 with Les femmes savantes or The Clever Women. Make no mistake about this, the stakes were high. Reputation is a form of gold in the republic of letters. Not only did these women, found mostly at royal court and in the salons of Paris, mean to attain the status of authors, they were at pains to replace the male concept of love – where the man gets to choose and the woman can merely assent or retreat (if she’s lucky). One reason that the Lake of Indifference is so large is that even today, we women keep watering it with our tears.

Madeleine de Scudery was born at Le Havre on the coast of Normandy, where her father was the port captain; her brother Georges would later hold a similar post in Marseilles. Left fatherless at age six and motherless shortly thereafter, Madeline and her brother were sent to live with an uncle. An enlightened man, he allowed the girl to receive a broad education including such non-traditional subjects as writing, Greek, and Latin. The girl was also free to study on her own, applying herself with zest to such like agriculture and medicine. After her uncle died in 1637, it was Madeleine who established a home for herself and Georges in Paris. He became a playwright and Madeleine wrote novels, including Artamène, which weighs in more than two million words, possibly the longest novel ever published.

For further reading: Precious Women by Dorothy Ann Liot Backer, New York, Basic Books: 1974.

Images:

1. Madeleine de Scudery - Carte du tendre, 1654, Bibliotheque nationale de france, Paris.'

2. Jean-Antoine Watteau - Sitting Couple, c. 1718, Aramnd Hammer Museum of Art, Los Angeles.

↧

↧

Love In The Desert

"In the desert, you see, there is everything and nothing.”

“It is God without mankind.”

- excerpts from A Passion in the Desert by Honore de Balzac, 1830, translated from the French by Ernest Dowson.

How ironic that Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman, both idiosyncratic film makers without whom post-WWII cinema would be the poorer, died on the same day - 30 July 2007. In his autobiography The Magic Lantern, Bergman dismissed the Italian director as an amateur and a man suffocated by boredom. Bergman was only slightly more gallant in his assessment of Antonioni's partner in his films of the early 1960s, Monica Vitti. Bergman was solely concerned with the question of God, For his part, Antonioni told the London Telegraph that Bergman’s only interest was finding answers from God, whereas he was content to explore metaphysical questions without offering answers. “You wonder what to look at. I wonder how to live. It’s the same thing,” he has a character say in Red Desert. Bergman the moralist admitted his past as a Nazi only in 1999; possibly it had slipped his mind for half a century, as he searched for certainty. As for the timing of their deaths, Bergman went first.

“I always had sympathy for young women of working-class families, even later when I attended university: they were more authentic and spontaneous.“ Antonioni told critic Aldo Tassone.

In 1964, Antonioni and his partner Monica Vitti had just completed the ‘Alienation Trilogy’ (L’aventura (1960), La notte (1961), and L’eclisse(1962). Their next project, and Antonioni’s first color film, Red Desert, would be awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

The son of a prosperous family from the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy, Antonioni was familiar with its poverty during and after World War II and then its seemingly miraculous prosperity, thanks to the booming petrochemical industry. The scale and dazzling variety of the structures erected, from factories to the row of red radio towers raised like so many giant beaks toward the heavens, inspired admiration and wonder, at the same time that they altered the landscape almost beyond recognition. All this went into the mise-en-scene that became Red Desert. When Antonioni tried to recall in a 1964 interview how many times he had been to Ravenna during his life, he could only guess “at least one hundred times.”

The film begins in soft focus, factories obscured by the mist from the Po River we assume, but Antonioni gradually reveals the steam clouds are belching from the smokestacks. Nearby, workers are on strike as a man shouts through a megaphone that conditions are so bad that the owner’s wife would be so ashamed of her husband that she would not show her face there. Then Giuliana, wife of the factory manager, appears walking with her little boy through this hellish-looking industrial wasteland. Throughout Red Desert, characters discuss the difficulty of hiring skilled workers, regardless of price. The strike that begins the film suggests film that prosperity does not, by itself, end exploitation.

Giuliana is gradually revealed to be a damaged soul. Hospitalized for a month following a near-miss deadly accident in her car, she has trouble reconnecting with everyday life. For a time, it seems that Corrado Zeller, a more sensitive colleague of her husband, may be able to help her but, in a manner all too familiar to novel readers (the character of Ralph Touchett in Henry James’ The Portrait of a Lady or Lawrence Selden in Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth) his offer of rescue is a mirage. Giuliana’s plight is eerily similar to other characters in Aontioni films. A woman vanishes from an island in L'Aventura, another woman evaporates into a crowd in Blow-up (1967), and in the penultimate shot in The Passenger (1975) a man simply vanishes as the camera makes a slow turn. We are all alone. Red Desert ends with the merest wisp of hope as Giuliana and Valerio stand again before the plant. When Valerio asks his mother if the birds know to avoid the poison pluming out of the smokestacks, she assures him they must know by now. This from Antonioni, a man enthralled by modern technology. Antonioni addressed his contemporaries with Red Desert but, from a distance of fifty years, it is easier to question the tradeoffs between middle class prosperity and a healthy environment that we have benefited from.In thrall to our devices, we walk around with our eyes on them, barely noticing nature much less other people

Although Antonioni denied being influenced by particular painters, in Red Desert, his first color film, he used painterly images and techniques throughout, whether or not the viewer is aware of them. To get the effects he was after, Antonioni had buildings, grass, and even trees painted. The crew spent one long night spraying trees with white paint to get the gray color the director wanted for a particular. When a bright blue stripe appears on screen we are alerted that the scene is shifting, so pay attention. Even the red of the title is muted by mist and dust. Giuliana, who plans to open a gallery where she will sell ceramics, paints the interior walls in blocks of soft and luminous color as though the room was a painting by Mark Rothko.

Did Antonioni read Balzac's story? Had he seen Giuseppe Vannucci-Zauli's architecturally plotted photographs? Possibly, given the photographer's reputation. In any case, Antonioni blocked out the movements of his characters with precision of an architect. In recent interviews Monica Vitti has described how the only directions he ever gave were “Look over here, turn your head, take the three and then stop.“ This method enabled the director to make extended takes, another way of shaping a scene.

Antonioni's characters have a way of becoming opaque, like the landscape in Red Desert. In L’Aventura, a woman vanishes from an island and is never found by her erstwhile friends. In Blow-Up a woman disappears into a crowd whose intentions dominate the film but are never revealed. And at the penultimate momen in The Passenger, a man vanishes before our eyes as the camera makes a slow turn.

Antonioni himself once defined the relationship between morality and science as being like that between modern men and women, meaning modern love. A good end point is Geogre Meredith's riveting sonnet sequenceModern Love, published in 1862. From it, comes this: "Ah, what a dusty answer gets the soul when hot for certainties in this our life."

Images:

1. Giuseppe Vannucci-Zauli (1917-1988) - Solitude, 1941, Alinari Archives, Florence.

2. Giuliana and Zeller walk by the radio towers, frame from Red Desert.

3.Giuliana and her son Valerio watch the strikers, frame from Red Desert.

4. The trees through the mist and pollution, from Red Desert.

5. Giuliana in her gallery, from Red Desert.

2. Giuliana and Zeller walk by the radio towers, frame from Red Desert.

3.Giuliana and her son Valerio watch the strikers, frame from Red Desert.

4. The trees through the mist and pollution, from Red Desert.

5. Giuliana in her gallery, from Red Desert.

↧

Ronsard: A Romance Of The Rose

Amid a thousand lawsuits, is it not the height of madness

To write about love?” – Pierre de Ronsard

No, a thousand times. The greatest French poet of the Renaissance, an omnivorous student of classical poetry, Ronsard "the schizophrenic," as Wyndham Lewis called him, combined within his verse-world the literary paganism of antiquity and the moral self-examination of his Catholic heritage. The same poet who could introduce himself to a beautiful woman by saying "I am Ronsard, I said - that is enough for you," could also write “(D)onnez-moi la force et le courage De contempler mon couer et mons corps sans degouts!” (Give me the strength and courage to comtemplate my heart and my body without mortification!)

Academics have estimated that more than 300,000 sonnets were produced by Europeans poets in the 16th century. Ronsard authored at least one thousand of them. Next to Shakespeare, he was the per-eminent poet of the age. And there may be a more intimate connection between the two. From Sonnet XXVI of the Second Book of Ronsard's finest work,Sonnets pour Helene (1578), are these lines that soound more than passingly similiar to Shakespeare's As You Like It (c. 1599)

“The world’s a theater, and mankind the players;

And Fortune, who is mistress of the stage,

Lends costumes, and Heaven and Destiny,

Are the great spectators of human life;”

Who was Helen that Ronsard should compose volumes in her honor? Both Helene de Sequere and Ronsard were employed by Catherine de Medici, Queen mother of France, at Fontainebleau in 1564. Apparently, Catherine encouraged their romance. Exactly what - or more precisely - how much happened is open to conjecture but Helene was concerned to protect her good reputation at court.. There is great sweetness in what little we do know. To read this is to sigh with envy across centuries.

“Once on a staircase in one of the royal palaces she allowed him to twine a thread of crimson silk round and round her arm while they talked. Once, in a kittenish mood, she powdered her hair and his beard with her own hair-powder, andce she made him a wreath of laurel.” (WL)

So who was Pierre de Ronsard? A younger son of the nobility from Vendome, he entered royal service at age twenty-two as page to Princess Madeleine. This promising career took him to Scotland, where on one trip, he met the young, beautiful Mary, Queen of Scots to whom he dedicated several poems. As befits a man known for his affection for his friends, Ronsard was with the doomed Mary in Fotheringay prison on the day she was executed. His father hoped that the young man would become a diplomat or a military officer but those hopes were dashed when Ronsard suffered an illness that left him partially deaf. He then entered minor clerical orders; he never became a priest, not being priest material. Ronsard idolized Horace, the Roman lyric poet, finding in the dicturm carpe diem, qusm minimum credula postero (seize the day, trusting as little as possible in the next one) a confirmation of his own youthful enthusiasm.

Where love is the subject of poetry, you often find roses, symbolic as well as floral. Think of Robert Herrick's "Gather-ye Rose buds while ye may," and then read Ronsard's bets known poem To Cassandra, where the rose is the mufti-purpose symbol of beauty in all its luscious brevity and eventual decay, the symbol of the flesh of a woman.

Which leads us to Cassandra, a real woman. She was fifteen when she met Ronsard on an April day, like another April day in 1327 when the Italian poet Petrarch met Laura. Avignon is no so far from the Chateau de Blois, after all, which is where Ronsard met Cassandra. His poems moved her but not so much to keep her from marrying someone else a year later. Cassandre was both nubile and virtuous. Between his poetic demonstrations of unruly passion and dazzling lyricism Ronsard assured readers by his frequent laments that he did not compromise her virtue. Decades later, in 1571, when Ronsard wrote Derniers vers pour Cassandre (Last Poem for Cassandra), he \ still remembered how deeply she had touched him

"Mignonne, allons voir si la rose

Qui ce matin avoit desclose

Sa robe de pourpre au Soleil,

A point perdu ceste vesprée

Les plis de sa robe pourprée,

Et son teint au vostre pareil.

Las ! voyez comme en peu d'espace,

Mignonne, elle a dessus la place

Las ! las ses beautez laissé cheoir !

Ô vrayment marastre Nature,

Puis qu'une telle fleur ne dure

Que du matin jusques au soir !

Donc, si vous me croyez, mignonne,

Tandis que vostre âge fleuronne

En sa plus verte nouveauté,

Cueillez, cueillez vostre jeunesse :

Comme à ceste fleur la vieillesse

Fera ternir vostre beauté." - A Cassandre by Pierre de Ronsar, 1545

"Mignonne, let us go see if the rose

that this morning did disclose

her purple robe to the Sun,

lost just before the day was dead

Her color as bright as yours?

Ah, See how quickly,

Mignonne, she loses them (her petals)

Ah, how her beauties drift down!

Ôh, truly monstrous Nature,

that such a flower only lasts

from morning just to night!

Therefore, if you believe me, Mignonne

While your youthful bloom

Is in its green freshness

pick, pick the flowers of your youth:

Before, like a flower, old age

will tarnish your beauty." - translation mine, J.A.L.

Called the "Prince of Poets" by his contemporaries, his reputation has had its ups and downs, mostly a matter of literary back-biting. There were those who condemned him while he lived for being highbrow and lowbrow at the same time. Ronsard had an answer for that, too.

“ It is better Rubampre, /To spend one’s life in business,/Or to sell one’s tongue for money /Before a purple Senate,/Than to follow the purple train/Of poor Calliope/ Why invariably allows the best singers of her troup/ To die of hunger.”

Called the "Prince of Poets" by his contemporaries, his reputation has had its ups and downs, mostly a matter of literary back-biting. There were those who condemned him while he lived for being highbrow and lowbrow at the same time. Ronsard had an answer for that, too.

“ It is better Rubampre, /To spend one’s life in business,/Or to sell one’s tongue for money /Before a purple Senate,/Than to follow the purple train/Of poor Calliope/ Why invariably allows the best singers of her troup/ To die of hunger.”

For further reading:

1.Ronsard by D.B. Wyndham Lewis, New York, Coward-McCan and Sheed & Ward: 1944.

2. Ronsard, Je dirai (in English)

Image:

1, Paul Serusier - Mignonne, allons voir si la rose, Fondation Bemberg, Toulouse.

↧

Never Lonelier: Gottfried Benn

"Never lonelier than in August:

Hour of plenitude – the countryside

Waving with red and golden tassels,

But where is your pleasure garden?

Soft skies and sparkling lakes,

The healthy sheen of fields,

But where is the pomp and display

Of the empire you represent?

Everything lays claim to happiness,

Swaps glances, swaps rings,

In wine breath, in the intoxication of things,

You serve the counter-happiness, the intellect."

“Never Lonelier” from Impromtus by Gottfried Benn, translated from the German by Michael Hofmann, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 2013.

When I studied literature in college, the German writer Gottfried Benn was the author of odd and disturbing short stories, one among several middle European writers (Georg Buchner, Heinrich von Kelist, Ilse Aichinger, Gerd Gaiser) who, taken together painted an unrelievedly dark picture of life. I still have that collection Great German Short Stories, edited by Stephen Spender.

Recently, I've been reading, as in picking up and putting down, a new translation of Benn's poetry (who knew?) by the German-born poet Michael Hofmann. In his introduction Hofmann writes "Benn can scarcely be said to exist in the English-speaking world." To Hofmann, Gottfried Benn is the most significant German poet of the 20th century after Rilke, and he may be right. Benn, though, is an entirely different sort Caught between the highbrow and the lowlife, Benn's first published volume was Morgue and Other Poems (1912), and the selections included in this new collection (Little Aster, Beautiful Youth, Circulation,etc.) are as grisly as you can imagine. A doctor who specialized in dermatology and venereal diseases, Benn didn't need his stint in the German Army during WWI to view the world through hostile eyes. That said, his early admiration for the Nazis, based partly on his oppositional bent, was not returned and he lived through WWII in bitter internal exile.

"I would be astonished if anyone were to read them," Benn wrote about his own poems in 1921, treating himself as though he were already dead. The real astonishment in reading a poem like "Never Lonelier" is the thought of how long Benn's work has been away.

Image:

Gustav Kampmann, Herbstabend (Autumn Evening,)) 1900, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

Kampmann (1859-1917) was a German artist who committed suicide by slashing his wrists after contracting an eye infection during WWI that made making art a misery.

Kampmann (1859-1917) was a German artist who committed suicide by slashing his wrists after contracting an eye infection during WWI that made making art a misery.

↧

Renoir And The Beauty Of The Ordinary

I grew up with Renoir's On the Terrace. A framed print was always in its place by my mother's dressing table. That it was not the original did nothing to keep me from falling in love with it. In my small world, it was a happy image of a mother and a daughter and I never questioned my assumption. Nor had I yet heard of Walter Benjamin and The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. If I had, I would have objected strenuously to any claim that the painting had been deprived of its aura in the process. But after seeing Renoir's La Parisienne, on tour from the National Museum of Wales and hearing the story behind it, I wanted to know more about my childhood Renoir.

According to Renoir, Chatou was “ the prettiest of all the suburbs of Paris.” Looking at just two of the pictures he painted there between the summer of 1880 and spring of 1881, no argument seems possible.

Luncheon of the Boating Party (now partof the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.)and On The Terrace also share a specific location: the terrace of the restaurant at the Hotel Fournaise. After his initial discovery of Chatou in 1875, Renoir often stayed at the hotel in the Parisian suburbs. In those days, Chatou was a popular place for rowing, as Argenteuil was for regattas, the same leisureactivities painted by seemingly every Impressionist. It helps to know that when Renoir painted what look like portraits to us, to his contemporaries they appeared rather as tableuax, or slices of life.

When these pictures were painted Renoir had recently exhibited his work at the First Impressionist Exhibition in Paris alongside pictures by Monet, Degas, Pissarro, and Morisot. At the time they had dubbed themselves teh Anonymous Society of Painters, but that didn't last long. The exhibition had been arranged by Paul Durand-Ruel, a dealer with galleries in Paris and London, who befriended many of the artists he represented.

When these pictures were painted Renoir had recently exhibited his work at the First Impressionist Exhibition in Paris alongside pictures by Monet, Degas, Pissarro, and Morisot. At the time they had dubbed themselves teh Anonymous Society of Painters, but that didn't last long. The exhibition had been arranged by Paul Durand-Ruel, a dealer with galleries in Paris and London, who befriended many of the artists he represented.

The members of the boating party are enjoying a convivial moment. contained by an overhead canopy and the terrace railings. In On the Terrace, the figures are contained but more subtly, by the railing behind them and the artist's decision to crop the image rather abruptly in front. In the time between these two paintings, Renoir had traveled to Algeria and critics have asserted a connection between the North African light and the luminosity that suffuses On the Terrace, as the reason that the inclusion of red roofs and blue hills in the distant background appears natural and unforced. The flowers on the child's hat and the balls of yarn in the basket may also have been a veiled personal reference by the artist. In 1879, one critic had dismissed a picture of Renoir's by saying it “seems to have bee constructed of different colored balls of wool.”

The painting was in progress on Easter Monday, 18 April 1881, when Renoir had the lunch with Whistler where the Frenchman announced that a planned trip to London would have to be postponed, as “I am engaged in a struggle with trees in bloom and women and children and can see no further than that at the moment...The weather is fine and I have my models; that is my only excuse.”

The pretty young woman in the red hat was Jeanne Darlaud, an eighteen year old from Limoges who had come to Paris to become a theater performer. The little girl in the blue hat has not been identified, but the two were not related, as an examination of their facial features makes plain. When it was finished, the picture became a favorite of Durnad-Ruel, who played a role in the confusion surrounding its subject. It was apparently Durand-Ruel who first called it Two Sisters,thinking that title would make it more salable than the one Renoir had chosen: Femme au bord de la Seine (Woman by the Seine). After it was shown at the Seventh Impressionist exhibition and the critics ridiculed the title as inapt, the dealer changed its title yet again, to On the Terrace. Georges Lecomte’s assessment was typical: The insinuating and crafty grace of her sly face is accentuated by the malicious obliquity and alarming smile in her eyes. She has the look of a modern Mona Lisa who knows all about love and seduction and is shamelessly flirting with you.” Then, as now, hope springs eternal in the male breast.

Confusion also has a long life, it seems. The Art Institute of Chicago, owner of On theTerrace, has a has produced a video that gives its title as Two Sisters and elaborates their relationship. Some stories are too good to let go.

Image:

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) - On the Terrace (a/k/a/ Two Sisters), 1871, Art Institute of Chicago.

↧

↧

The Popular Poplar

Were there poplar trees in the mythical world of the Greek god Apollo? The terrain of Mt. Parnassus, Apollo's earthly home, is rugged, suggesting great age. But it suited the taste of the arch-Romantic painter Gustave Moreau to imagine poplars there. And it suits our imagination too, to think of the youthful (beardless) Apollo surrounded by lush greenery. From the Roman poet Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, we have the fullest account of the adventures of Apollo and Pegasus, the winged horse who created the Hippocrene springs with a well-aimed kick of the hoof.

Poplars and art have had a long and intimate relationship. Before canvas became the preferred medium for painting in the 16th century, artists painted on wooden panels made from poplar. That most famous painting of the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa was painted in oil on white Lombardy poplar.

Now, another question. Why are there so many poplar trees in French painting? The answer is more than botanical. Because the poplar, or peuplier in French, shares its etymological ancestry with the Latin word populus. When the Revolution began in 1789, this... tree became the symbol of the new republic, the “arbre de la liberte” (the tree of liberty). Louis XVI must have understood the symbolism when he bowed to pressure to preside at a ceremony when a poplar was planted in sight of his royal palace. After Louis was cut down by the guillotine in 1793, the tree was cut down, apparently being one of those trees that grows “only when watered by the blood of tyrants.”

For several decades, the symbolic value of the poplar was jealously guarded by whatever regime was in power. After a man in the Vaucluse cut down a poplar, sixty-three neighbors who concealed his identity from the authorities were murdered, their houses burned, and their fields poisoned with salt. When Napoleon declared himself Emperor, he took care to re-christened it as the arbre Napleon.

Poplars were planted along rural roads and at the entrances of estates alike. Their stately rows were visually impressive and served usual functions: as windshields, and markers of property lines, and when planted along river banks, poplars provided a measure of flood control. As one of his early official actions, when Louis XVIII reinstated the monarchy he ordered a tree census that counted at least sixty thousand poplars in France. But with passing time the popular poplar blended into the landscape as one among many trees.

And then there was Claude Monet. Who better than an Impressionist to experiment with the effects of light in changing weather by painting the same scene again and again? By the summer of 1891 when Monet began his series of polar paintings (twenty-five in all) he had been collecting Japanese prints for two decades; in photographs the walls of his home at Giverny were covered with them. Théodore Duret, a journalist and art critic who had visited Japan in 1871-72, wrote that Monet’s poplar series was inspired by Hiroshige's Numazu, Yellow Dusk, a work with a sweeping curve of trees, emphasizing the decorative patterns found in nature. Whether or not Duret was correct, you can see what he meant by looking at the paintings.

The maxim that we should not assume that a painter did not see what (s)he did not paint applies to Monet's poplars. Painting on his bateau atelier, a houseboat anchored in the river, Monet would have viewed the shore from a low perspective, but stretching the trees off the top and bottom of the canvas was his way of intensifying their dramatic profiles against the sky. The triangular wedge of trees in the background was, in fact, poplars lining the road; in Monet hands this accident of landscape becomes an elegant decorative gesture, one that changes with the seasons from summer to autumn.

When we refer to these trees as Monet's, it was more than a figure of speech at the time.. The poplars were located on communal land near the village of Liimetz, just upstream from Giverny. It was a marshy area, made intriguing visually by the way the river Epte curved back on itself in an s-shaped curve, bot once but twice. Shortly after Monet began to paint them, village officials announced plans to auction the trees off, having planted them as a cash crop that was now ready to be harvested. On July 28, Monet anguished over the “quantities of new canvases I must finish.” His pleas to the mayor of Limetz failed, Monet arranged to purchase the trees with a partner who would delay the harvest until Monet had finished. Meaning that soon after the paint had dried, no one could go to see what the artist had painted.

It is charming to imagine Monet leaving home before sunrise to scout a good view, loosening the rope that moored his rowboat to shore, and then rowing upstream through the mist to the spot in the Epte where his houseboat sat at anchor. Charming and not far-fetched, as Monet has left us evidence of what he saw on his way to Limetz, like Morning on the Seine near Giverny (1897) in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That he brought his canvases back to the studio for finishing takes nothing away from them. Among the pleasures of looking at Monet's poplar pictures we can see not only the passing of time but the mapping of history on the French landscape.

Images:

1. Gustave Moreau (1826-1898) - Apollo and Pegasus, Musee Gustave Moreau, Paris.

2. Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875) - Canteleu pres de Rouen, Musee du Petit Palais, Paris.

3. Camille Pissarro - Poplars - Sunset at Eragny, 1894, Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City.

4. Claude Monet - Poplars - Grey Weather, 1891, private collection.

5. Claude Monet - Les quatres arbres (The Four Trees), 1891, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

4. Claude Monet - Poplars - Grey Weather, 1891, private collection.

5. Claude Monet - Les quatres arbres (The Four Trees), 1891, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

↧

Pierre Bonnard: Painter Of The Future

“But the painter of the future will be a colorist such as has never yet existed.” - Vincent Van Gogh to his brother Theo in a letter dated 5 May 1888.

“Society was ready to welcome Cubism and Surrealism before we had reached our objective. We found ourselves in some sense suspended in air.” – Pierre Bonnard

The mimosa is a sensitive plant; it droops when touched. So, by most accounts, was Marthe de Meligny (1869-1942), for thirty years the mistress and then for twenty years more the wife of French artist Pierre Bonnard. If we have learned anything in these recent decades of re-examining the place of women in the history of art, we should be skeptical about the role assigned to the wife of a male artist.

Marthe, Bonnard's favorite model, appears in Woman With Mimosa(above). A lovely example of a hybrid genre Bonnard seems to have created, the painting is neither a portrait or a still life. On the Cote d'Azur where Pierre and Marthe lived, the mimosa blooms in January and here it frames the her face with Bonnard's favorite color, Naples yellow. I do not want to characterize her expression, although male critics have been fearless in this regard. The averted gaze of a woman or, in the paintings of Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershoi the turned back, is seen as a problem requiring a solution. It is worth noting at this point that, in his paintings and even more remarkably in his photographs of Marthe, even when nude, Bonnard conveys her sensuality with discretion. Unlike, say, the nudes of his contemporary Edgar Degas, Bonnard's never seem a violation of privacy. The pensive, sidelong gazes of many figures in Bonnard's workreminded the artist's great-nephew Michel Terrasse of Giotto's profiles or the enigmatic faces of figures in medieval frescoes.

The story of modernism made no room for Bonnard. Bonnard's work can be difficult to pigeonhole, an annoyance to art historians who like their artists neat. He experimented with light but he was no Impressionist. Bonnard rarely painted outdoors, saying “It’s not possible; the light changes too quickly.” He preferred to rely on drawings as aides memoires to locate what he called the 'idea' or the 'seduction' for each picture, the painterly equivalent of the donnee for the author Henry James. Although his work is well known, Pierre Bonnard remains elusive. There is as yet no Bonnard biography and writers of monographs and museum catalogs continue to recycle anecdotes of doubtful accuracy.

It did not help Bonnard’s reputation that Pablo Picasso, his contemporary and a commanding presence in 20th century art, mocked Bonnard’s paintings publicly and encouraged his supporters to do the same. Henri Matisse, who had become close to Bonnard in their later years in southern France, was stung into an angry defense when one such article appeared in Cahiers d’Art shortly after Bonnard's death in 1947. “ I cannot understand why you went after Bonnard. I know Bonnard. I have been watching him for half a century. I was never able to discover the depths of his expression even though it is constructed from materials I know well.”

Born at Fontenay-aux-Roses, surely the most evocatively named of Parisian suburbs, Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) studied art at the Academie Julian in Paris. There he mat Marie, who went by the name Marthe in 1893.

"There is always color, it has yet to become light." - Pierre Bonnard

The couple began to winter in Provence in 1914, and its effect on Bonnard's use of color was emphatic; it has been compared to the heavenly light in Renaissance religious painting. Bonnard found a house at Le Cannet in 1922 and by 1926, he had saved enough money to purchase it. He christened the house Le Bosquet and painted the exterior stucco in pink.

Several room he painted in Naples yellow, a shade that appears to capture the moving sun in paint. “I don't like to paint in grand rooms; they intimidate me. My luxury is my painting.” This from the artist who pinned his canvases to the walls of his studio. “It would bother me if my canvases were stretched onto a frame.” That way he could allow himself to discover its finished size.

The colors of the mimosa, the eucalyptus, and the olive tress in the garden at Le Bosquet are all present in The Dining Room Overlooking the Garden, a correlation with Bonnard's idea that we take in a scene all at once when we first look at a painting.

"Art is not nature. There is also much more to be had from color as a means of expression." - P.B.

That "more" includes the painting of light so that it seems to emanate from within the canvas. In this, the American painter Mark Rothko would seem an heir to Bonnard. Also, to Rothko, as to Bonnard, paintings were meant for quiet contemplation. This is what Bonnard had in mind when he said, "The museums are full of uprooted paintings," an assessment that Andre Malraux explore at length in his 'Museum without Walls ' in The Voices of Silence.

For further reading:

1. Bonnard at Le Cannet by Michel Terrasse, translated from the French by Sebastian Wormell, New York, Thames & Hudson: 1993.

2. Bonnard by Julian Bell, London, Phaidon Press: 1994.

3. Bonnard: Shimmering Color by Michel Terrasse, translated from the French by Laurel Hirsch, New York, Harry N. Abrams: 1999.

Images:

1. Pierre Bonnard - Woman With Mimosa, 1924, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

2. Pierre Bonnard - Nude Dressing, 1925, Galerie Krugier & Cie, Geneva.

3. Pierre Bonnard - Dining Room Overlooking the Garden, c. 1930, Museum of Modern Art, NYC.

4. Pierre Bonnard - The White Interior, 1932, Musee de Grenoble.1. Pierre Bonnard - Woman With Mimosa, 1924, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

2. Pierre Bonnard - Nude Dressing, 1925, Galerie Krugier & Cie, Geneva.

3. Pierre Bonnard - Dining Room Overlooking the Garden, c. 1930, Museum of Modern Art, NYC.

5. Mark Rothko - untitled , 1968, Fondation Beyeler, Basel.

↧

The Exquisite Awkwardness Of Georges Lacombe

Finistere – finis terre – land's end – the end of Europe.

![]() A peninsula inhabited by humans for 2.5 million years, Brittany is also inhabited by all manner of mythical characters, pixies, mermaids, giants, and sailors who landed in boats made of leaves or stone. They were missionaries of a rude sort, come to bring a new religion to the locals who proved themselves to be wicked by fighting back with the assistance of demons and serpents. How apt then is the enduring myth of the drowned the City of Ys, said to be located offshore in the Baie de Douarnenez, a city brought to ruin by a spoiled princess (Dahout) who convinces her father the King (Gradlon) to build her a magnificent churchless city on the waves. Needless to say, the story ends badly. And can it be only coincidence that the brilliant Breton writer Chateaubriand (1768 – 1848) gave his 42-volume autobiography the title Memoirs d'Outre-Tombe (Memoirs From Beyond theGrave) ? Here also the ghosts of the star-crossed lovers Tristan and Yseult and the jilted King Marc of the Roundtable roam.

A peninsula inhabited by humans for 2.5 million years, Brittany is also inhabited by all manner of mythical characters, pixies, mermaids, giants, and sailors who landed in boats made of leaves or stone. They were missionaries of a rude sort, come to bring a new religion to the locals who proved themselves to be wicked by fighting back with the assistance of demons and serpents. How apt then is the enduring myth of the drowned the City of Ys, said to be located offshore in the Baie de Douarnenez, a city brought to ruin by a spoiled princess (Dahout) who convinces her father the King (Gradlon) to build her a magnificent churchless city on the waves. Needless to say, the story ends badly. And can it be only coincidence that the brilliant Breton writer Chateaubriand (1768 – 1848) gave his 42-volume autobiography the title Memoirs d'Outre-Tombe (Memoirs From Beyond theGrave) ? Here also the ghosts of the star-crossed lovers Tristan and Yseult and the jilted King Marc of the Roundtable roam.

![]() Images:

Images:

1. Georges Lacombe - Marine bleue - Effet de vagues, 1893, Musee des Beaux-Arts, Rennes.

2. Georges Lacombe - Falaises a Camaret, c. 1892, Musee municipale, Brest.

3. Georges Lacombe - Breton Boatwomen - c. 1888-99, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

4. Georges Lacombe - Existence, c. 1894-96, carved walnut, Musee d'Orsay, Paris.

5. anonymous Breton artists -Sujet allegorique, c. 1500, Musee de Louvre, Paris.

A peninsula inhabited by humans for 2.5 million years, Brittany is also inhabited by all manner of mythical characters, pixies, mermaids, giants, and sailors who landed in boats made of leaves or stone. They were missionaries of a rude sort, come to bring a new religion to the locals who proved themselves to be wicked by fighting back with the assistance of demons and serpents. How apt then is the enduring myth of the drowned the City of Ys, said to be located offshore in the Baie de Douarnenez, a city brought to ruin by a spoiled princess (Dahout) who convinces her father the King (Gradlon) to build her a magnificent churchless city on the waves. Needless to say, the story ends badly. And can it be only coincidence that the brilliant Breton writer Chateaubriand (1768 – 1848) gave his 42-volume autobiography the title Memoirs d'Outre-Tombe (Memoirs From Beyond theGrave) ? Here also the ghosts of the star-crossed lovers Tristan and Yseult and the jilted King Marc of the Roundtable roam.

A peninsula inhabited by humans for 2.5 million years, Brittany is also inhabited by all manner of mythical characters, pixies, mermaids, giants, and sailors who landed in boats made of leaves or stone. They were missionaries of a rude sort, come to bring a new religion to the locals who proved themselves to be wicked by fighting back with the assistance of demons and serpents. How apt then is the enduring myth of the drowned the City of Ys, said to be located offshore in the Baie de Douarnenez, a city brought to ruin by a spoiled princess (Dahout) who convinces her father the King (Gradlon) to build her a magnificent churchless city on the waves. Needless to say, the story ends badly. And can it be only coincidence that the brilliant Breton writer Chateaubriand (1768 – 1848) gave his 42-volume autobiography the title Memoirs d'Outre-Tombe (Memoirs From Beyond theGrave) ? Here also the ghosts of the star-crossed lovers Tristan and Yseult and the jilted King Marc of the Roundtable roam.How curious that the French artist Georges Lacombe is best known for one of his least typical works, a painting that translates the rugged coast of Brittany into the visual vocabulary of ukiyo-e prints. In Marine bleue – Effet de vagues the waves breaking on the shore at Finistere seem to have arrived from Japan. The high horizon, a certain flatness not seen in realist or Impressionist seascapes, announce the influence of a style the French dubbed japonisme. Decorative fat pink clouds and peacock-feathered are not typical of Brittany, a land of rocky outcroppings incised by waves whose decorative effect, if that is what it was, whose coast is more prehistoric-looking than decorative.

What is attractive in Lacombe's paintings is their liveliness. Again in Breton Boatwomen we confront a subject that is treated more dourly in paintings of his contemporaries, notably his close friend Charles Cottet. Here the women are not waiting by the shore for bad news of their sailor husbands and sons; they come alive through purposeful rhythm as active rowers.

What is typical of Lacombe the artist is that he was not a Breton native; rather he came from a prominent family of Versailles, no small distinction in a royal seat. The laying down of railroads from Paris to the ends of 19th century France opened the way for tourism and artists were prominent among them. For nine years from 1888 to 1897, Lacombe summered in Brittany with his artist friends Paul Serusier and Emile Bernard. Lacombe was the lucky one, with inherited wealth and an advantageous marriage, he had no need to sell his work. Rather, he chose to give it away. If his landscapes look familiar, it may be because the young Lacombe had been a member of Les Nabis, where he got to know Maurice Denis, whose coastal landscapes are similarly colorful. Unlike the devout Denis, Lacombe was decidedly anti-clerical.

Within the group Les Nabis, Lacombe was dubbed the "sculptor Nabi." Whether working with wood or paint, Lacombe

What is attractive in Lacombe's paintings is their liveliness. Again in Breton Boatwomen we confront a subject that is treated more dourly in paintings of his contemporaries, notably his close friend Charles Cottet. Here the women are not waiting by the shore for bad news of their sailor husbands and sons; they come alive through purposeful rhythm as active rowers.

What is typical of Lacombe the artist is that he was not a Breton native; rather he came from a prominent family of Versailles, no small distinction in a royal seat. The laying down of railroads from Paris to the ends of 19th century France opened the way for tourism and artists were prominent among them. For nine years from 1888 to 1897, Lacombe summered in Brittany with his artist friends Paul Serusier and Emile Bernard. Lacombe was the lucky one, with inherited wealth and an advantageous marriage, he had no need to sell his work. Rather, he chose to give it away. If his landscapes look familiar, it may be because the young Lacombe had been a member of Les Nabis, where he got to know Maurice Denis, whose coastal landscapes are similarly colorful. Unlike the devout Denis, Lacombe was decidedly anti-clerical.

Within the Nabi group, Lacombe was nicknamed "the sculptor Nabi." Whether working with wood or with paint, Lacombe's style owes something to Paul Gauguin's stylized vision of primitivism, but Lacombe was capable or more accomplished draftsmanship. Existence is one of four panels Lacombe carved in walnut for the bed in his stduio at Versailles. Created during the decade he when he summered in Brittany, theyare earthy, somewhat crude amalgams of le style primitive and Breton folk art. The side panels are images of a married couple at the beginning and again at the end of their life together; the headboard shows birth.

Existence (above) is a compact treasury of archaic references. It is amazing. Framed by a serpent biting its own tail (Ouroboros, from the Greek,symbol of cyclic recreation), at the same time the double loop suggests a pair of eyes. Below the eyes is what looks like a voluptuous pair of lips. Buried within this frame is an embracing couple and the meaning is underlined when you learn that the scored leaf at left symbolizes the female sex organs. More easily recognizable are the spermatozoids spurting from the four corners of the frame. This type of overtly sexual symbolism shows up shortly in the mosaic style paintings of women by the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt. Lacombe never displayed the panels in public and they remained in the artist's family until 1956.

In November, 2012, a rare retrospective The Plural Universes of Georges Lacombe opened at the Musee Maurice Denis, in cooperation with Musee Lambinet at Versailles, a gesture of admiration and affection for the artist and his two homes: Versailles, the heart of royal Franmce and Brittany, its Atlantic extremity, finistere.For further reading: Les univers de Georges Lacombe by Gilles Genty, et al, Musee departmentale Maurice Denis, Saint- Germaine-en-Laye.

Images:

Images:1. Georges Lacombe - Marine bleue - Effet de vagues, 1893, Musee des Beaux-Arts, Rennes.

2. Georges Lacombe - Falaises a Camaret, c. 1892, Musee municipale, Brest.

3. Georges Lacombe - Breton Boatwomen - c. 1888-99, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

4. Georges Lacombe - Existence, c. 1894-96, carved walnut, Musee d'Orsay, Paris.

5. anonymous Breton artists -Sujet allegorique, c. 1500, Musee de Louvre, Paris.

↧

My Vegetable Love: Rufino Tamayo

“I woke from a dream that all my friends were scallions

I heard bravos from the lumps of beef I had left behind

From the ground round porterhouse and tartar

As they cleaved like peas and sent out shoots.

The sprouts I had eaten

Rejoiced within the striations of my iris

Arched in delight tickling tight curls of chromosomes.

I read leaves in a wadded lettuce heart

for news of the world

I dug up sweet tuberous poems

I discovered myself counting the chambers in a tomato

I made ink from spores I signed my checks with it

The day I became a vegetarian

I found letter from all the fish in the seas."

- Fredrich Steinway, reprinted from Food for Thought: An Anthology of Writings Inspired by Food, edited by Joan & John Digby, New York, William Morrow and Company: 1987.

It is easy to name the sources that plants rely on in order to flourish: sunlight and water, or more poetically, in the words of the French writer Andre Gide, "les nouritures terrestres." In trying to identify the wellspring of human affections we become Aristotelians; that is we accept his taxonomy of souls (vegetative, sensitive, and rational) and optimistically choose the vegetative because it embodies growth. This is what the poet Andrew Marvell was getting at in "To His Coy Mistress" (1681) when he described his "vegetable love."

As in Plato's allegory of the cave, the sun is unseen in the paintings of the late Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo but we intuit its presence in the luminous quality that the artist bestowed on his watermelons, painted over and over again but never more effectively than this version from 1965.

Image:

Rufino Tamayo (1899-1991) - Sandias (Watermelon), 1965, private collection, current whereabouts unknown

↧

↧

Niki de Saint Phalle: The Revolutionary Colors Of Joy

"‘On a psychological level I have all that it takes to be a terrorist, but instead I decided to use guns for good, for art. " - Nike de Saint Phalle (1930-2002)

Larger-than-life papier mâché sculptures, experimental films, performance art (shooting at paint-filled bags against a canvas): from all this, a selection of some 200 works that can fit inside a museum are on display this autumn in Paris at the Grand Palais, all by the Franco-American artist Niki de Saint Phalle

Born in Neuilly-sur-Seine and raised in New York, Niki de Saint Phalle was the daughter of a French aristocrat and an American heiress. A teenager with the angelic face, Niki modeled for such international magazines as Elle, Harper's Bazaar, Vogue, and Life. She refused the role of Queen Guinevere inRobert Bresson's1974 film Lancelot of the Lake.

In the meantime, by the age of twenty-three she was married (to the writer Harry Mathews) and the mother of two children, when she had a nervous breakdown. While hospitalized for six weeks in Nice, she began to paint. Niki de Saint-Phalle said that painting provided a way to domesticate her demons. “Without this, I do not like to think of what might have happened to me.”

Her early canvases were large, featuring drippings on a black background, more like speckles and flecks of color than the rivulets made by Jackson Pollock. Saint Phalle also pasted various objects onto her canvases; her work came to be seen as part of Pop Art or the French Nouveau Reailsme, a group in which she was the only female member..

In 1955 while in Barcelona, Saint Phalle visited the Parc Guell where she saw the fantastic architecture of Antonion Gaudi, The experience energized her to work, leading in her first exhibition the next year at St. Gallen, Switzerland.

Her partnership with the artist Jean Tinguely (they married in 1971), which began in 1960 took on a mythical aspect. They were dubbed " the Bonnie and Clyde of modern art" after a series of happenings (Tirs) where audience members were invited to fire guns at paintings. Their joint creations, large and colorful, occupied public spaces (the Fontaine Stravinsky in front of the Center Pompidou 1983). Her monumental Tarot garden that opened in Tuscany in 1998 was inspired by Parco del Mostri (Park of Monsters) in Bomarzo and by the Watts Towers of Simon Rodda which she had visited in February 1962.

I

Saint Phalle had the original idea for the Nanas in 1965 while a friend was pregnant. The Nanas undermined the myth oa all-powerful masculinity with glee and seriousness. The first Nanas, such as Benedicte, was the prototype of these giant sculptures, multicolored paper, glue, wool and resin. Through their immense bodies the artist re-imagined the idea of a matriarchal society. The largest Nana was Hon, a reclining figure that filled on entire hall at the Moderna Museet (Stockholm) created with Jean Tinguely and Per Olof Ultvel, in 1966. The figure was destroyed at the end of the exhibition.

The next year at an exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam Saint Phalle announced: "Power to the Nanas. We have Black Power, so why not Nana Power? It really is the only possibility. Communism and capitalism have failed. I think that the time is ripe for a new matriarchal society.”

A dark undercurrent runs through Saint Phalle's work; she used bright colors and joyous fervor to deal with painful experiences like pregnancy, failed love, incest, and violence. n 1972, when Saint Phalle made her first feature film Daddy she alluded for the first time to the father-daughter incest she suffered when she was eleven. She wrote about it directly in her book My Secret (1994).She was not afraid to express "unfeminine" emotions like frustration and rage at the forces that economic and gender inequality. She made her art from no small plans. La Cabeza,a late work inspired by the Mexican day of the Dead, occupies a prominent place in the current exhibition, perhaps the artist's meditation on the respiratory illness caused by the effects of the materials she had worked with for so long.

Art is not timeless, it must transcend time if it is to speak to new viewers, argued Andre Malraux in Voices of Silence. The art of Niki de Saint Phalle does. Saint Phalle lived in a moment of optimism, a moment where possibility seemed to be exploding with a big bang, after being pent up by decdaes or war and depression. She used imagery and ideas with an enthusiasm that is often absent from art today. This too is a moment and her work is here to remind us that more things are possible than any one moment can contain.

Niki de Saint Phalle, born October 29, 1930.Images:

1. Peter Whitehead - Niki de Saint Phalle, 1972, Grand Palais, Paris

2. Niki de Saint Phalle - L'aveugle dans la prairie ou L'homme et la vache (The Blind Man on the Prairie or The Man and the Cow) Pompidoui Center, Paris.

3. Niki de Saint Phalle - Nightscape, c.1958, Sprengel Museum, hanover.

4. Jill Krementz - Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely, no date given, Grand Palais, Paris.

5.Niki de Saint Phalle - Benedicte, 1965, private collection, photo by Laurent Condominas, Grand Palais, Paris.

6.Niki de Saint Phalle -La Cabeza or Head of Death, 2000, Grand Palais, Paris.

7. Nike de Saint Phalle, Temple of All Religions, Sprengel Museum, Hanover.

8. Nikie de Saint Phalle - La fontaine de Nana (The Nana Fountain), c. 1998, Garavicchio.

↧

An Autumn Anachronism

“My fear is that in the depth of night,