"Your paintings are just like my films. About nothing. But with precision." - Michelangelo Antonioni to Mark Rothko, in conversation at Rothko's New York studio.

Whatever they are called, Anontioni's early films have fallen into neglect; even the director's death in 2007 at the age of ninety-four has failed to spark a reconsideration. The standard explanation is that the word "alienation," an amorphous term at best, has become old-fashioned, associated with the zeitgeist of the 1960s, in a word - passe. It has been replaced by a stew corrosive irony and vapid hipness. In his always entertaining

Hip: A History (2004), John Leland preferred to focus on the makers (Transcendentalist writers and black jazz musicians) and the technical gadgets, while finessing consumerism, the real mechanism that spread hipness. Before you dismiss the dazed wanderers searching on an island for a missing woman (

L'Avventura) or a woman walking, seemingly aimlessly, through an urban wasteland (

L'Eclisse), ask yourself if they look much differently from contemporary pedestrians wandering in front of moving vehicles, their eyes glued to the cell phones in their hands. Do we really have nothing more to learn from Antonioni?

![]()

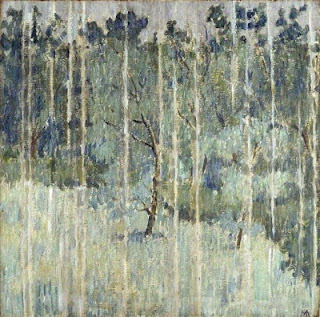

II. - Critics have made much of Antonioni's use of architecture in his films, the late Peter Brunette, going so far as to say that Antonioni's framing of shots is so masterful that you could isolate almost any one individually and hang it on a wall as a work of art. But this is not only about architecture and not only about modernism. Antonioni was an amateur painter who constructed miniature buildings as a child and admired the abstract-expressionist Mark Rothko. Did he associate Rothko's multiform blocks of color with the blocks of color used by the Italian Macchiaioli painters of the late 19th century? It seems possible. His use of painterly abstraction in his films looks inevitable in the rear-view mirror of time.

But Antonioni the boy who loved drawing and then the teeanger who fell in love with cinema, grew up to earn a degree in economics. A scene in L'Eclisse was set in the Borsa, a modern building that replaced an antique monument to the Emperor Hadrian, a man keenly interested in architecture, as Antonioni surely knew. Antonioni shows us the stock exchange in its usual mood of hysteria, speculators screaming orders to buy and sell; he makes us see a familiar scene as it might look to a visitor from another world – unintelligible and, therefore, meaningless. As he often does, Antonioni marks a change abruptly by means of a caesura, with a brief silence on the trading floor as traders pa respects to a recently deceased colleague, Thirteen years later, in an interview, Antonioni stated that he had intended this scene to show capital being shifted from production to speculation, “signs of violence that are connected to money…..I would say that The Eclipse is still a modern film in that its protagonists are people who do not believe in feelings – that is, they limit them to certain things.” Whatever his views of the middle class had been in the early 1960s, by 1975 he saw signs of deterioration and anger.

![]()

III. - "I am not a moralist, and my film is neither a denunciation nor a sermon. It is a story told in images whereby, I hope, it may be possible to perceive not the birth of a mistaken attitude but the manner in which attitudes and feelings are misunderstood today." - Michelangelo Antonioni speaking at the press conference following the premier of L'Avventura at the Cannes Film Festival in 1960.

When L’Avventura premiered it caught viewers unawares, its style was so unexpected, especially to fans of his earlier pictures. The audience at Cannes was divided, some applauding vigorously, some booing the director. Moniica Vitti left the auditorium in tears. The festival jury was also divided; it awarded a jury to prize to L'Avventura and gave the coveted Palme d’Or to Federico Fellini's La dolce vita. American critics were not impressed, led by the influential Bosley Crowther of the New York Times who sneered that the film looked like a few reels had been lost.

Critics had the opposite complaint two years later when L'Eclisse was released, that the final eight minutes should have been lost, and those minutes have been excised from a number of prints. The twilit streets caused by the eclipse are largely empty save for blinking street lights, a passing bus, and a man reading a newspaper headline about atomic energy. This is the landscape that the lovers, Vittoria and Piero or Vittoria and Riccardo, once inhabited. The wooden fence and the rain barred remain, eerie reminders of everyday life.

“I especially love women,” he has said. “Perhaps because I understand them better? I was born amongst women, and raised in the midst of female cousins, aunts, relatives. I know women very well. Through the psychology of women, everything becomes more poignant. They express themselves better and more precisely. They are a filter that allows us to see more clearly and to distinguish things.” – M.A.

It would be an anachronism to label Antonioni a feminist filmmaker. His contemporaries sensed a cliched battle of the “feminine” life force with the natural world versus the patriarchal poisoning of nature. I prefer the analogy represented by the saying that the slaves always know more about the masters than the masters know about the slaves.

![]()

IV. - Lack of communication and understanding between lovers parallels the disconnect between society and nature. The first theme dominates La Notte where the married couple of Lidia and Giovanni reckon with their emotional estrangement through the death of a close friend and their encounter at an all-night party with the host’s daughter. In L'Eclisse the themes merge, and in Red Desertthe devastated landscape dwarfs human despair. In retrospect, Red Desert was the period; Antonioni left for England where he made his first non-Italian film, the classic Blow-Up (1966). Almost twenty years passed before he returned to film in Italy again, in 1982 making Identificazione di una donna (Identification of a Woman), a film about an aging director.

Nanni Moretti, in Sight & Sound, once said that lovers of Italian films come in two varieties: admirers of Fellini's egocentric but kind-hearted world and those who prefer Antonioni's austere modernism and his characters with their endless existential angst. Antonioni’s didactic methods yielded few answers but have stimulated many discussions.

Monica Vitti was Antonioni's collaborator on the movies they made together. If Antonioni’s camera gazes at Vitti, Vitti gazes back; it is through her eyes that we witness the scene at the stock exchange, it is her consciousness that takes in the urban landscape and despoiled nature. When Antonioni was introduced to Vitti, she was a stage actress, particularly admired for her comedic style in the boudoir farces of Georges Feydeau (1862-1921). Her beauty, which is undeniable, is simply there. After their relationship ended, Vitti worked with other directors, including Luis Bunuel, and made her debut as a director in 1989 with Scandalo Segreto.

![]()

Returning to where we started, the meeting between Antonioni and Rothko, let me add Antonioni's description of Rothko's work: "It's painted anxiety." In Red Desert, the character Giuliana attempts to regain her bearings by opening an art gallery where she paints in the "Rothko" style. Watching Red Desert makes me regret that Antonioni lacked the funds to make all four of these films in color.

For further reading:

The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni by Peter Brunette, Cambridge and London, Cambridge University Press: 1998.

Images: stills from the films

1. Monica Vitti in

Red Desert, 1964.

2. Monica Vitti in

L'Avventura, 1960.

3. Monica Vitti in

La Notte, 1961.

4. Monica Vitti and Alain Delon in

L'Eclisse, 1962.

5. Monica Vitti in

Red Desert, 1964.

![]()

![]()