One of the decisions I had to make in choosing the layout for this website was whether the background should be dark or light. Which would better complement the images and which would make the text easier to read? If there wasn’t a solution that harmonized both, then what? If there had been an off-white shade, perhaps slightly textured, I would have picked that because it works well for looking at art in person. A flat white background produced an ambiance similar to the experience of looking at art in museums where thehard surfaces (stone, concrete, and marble) favored by contemporary architects create a harsh environment, leaching color from works that were never intended by their creators to be viewed in the equivalent of a commercial coliseum. Minimalism, relying as it does on maximally sized works, has contributed to the popularity of large featureless spaces that dwarf all other artworks.

Two new museums opened in 2001, one in New York and the other in Vienna, that offer an illustration of the ways that the arrangement of artworks affects our response to them. Surprisingly, it is the museum in midtown Manhattan that does the better presentation of fin-de-siècle Vienna.

The Leopold Collection, located in Vienna’s historic district, now its Museumsquartier, was built after not one but two, architectural competitions and the resulting museum is as unsatisfactory as you might expect given its genesis. High ceilings and often harsh lighting dwarf the paintings of Klimt, Moser, and Schiele and the interspersed Wiener Werkstatte furniture looks like toys from a doll’s house, robbed of a sense of their intended scale in its large featureless galleries.

In contrast, the Neue Galerie is housed in a 1914 Beaux-Arts townhouse on Museum Mile, within sight of the Metropolitan Museum. Its original architects were Carrerw & Hastings, the firm that designed the Frick Museum and the New York Public Library, also on Fifth Avenue. Longtime friends and collectors of Viennese art, Ronald S. Lauder and Serge Sabarsky chose the German-born architect Annabelle Selldorf to direct the renovation from residence to museum. In the original marble mantels, sinuous wrought-iron stair surrounds, and the elegant grids that cover the air ventsSelldorf recognized elements of a total aesthetic compatible with Viennese Art Nouveau, the basis of the Neue Galerie's permanent collection.

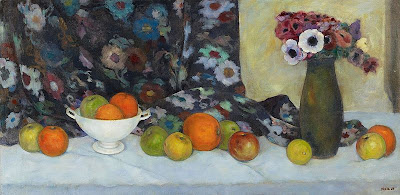

Which brings us to the paintings of Koloman Moser reproduced here. If Moser’s landscapes remind you of Ferdinand Hodler’s paintings of Switzerland or his flower paintings make you think of the late flower paintings of Edouard Manet, you have identified the major influences on Moser's paintings. Moser had become accustomed to working within a square format as designer for Ver Sacrum, the journal of the Vienna Secession. The grid pattern on the ceramic jug is an allusion to the movement's introduction of geometric patterns into the mixture of Art Nouveau.

These paintings are small (2.5 centimeters = I inch) but you can’t see the individual sizes or relative sizes of images on the internet. This is hardly a new problem; it is one that has bedeviled art book editors for decades. Museums with have greater latitude for making arrangements of artworks on display don't necessarily get it right either. And that is why I posed the question in the title of this post.

Viewing artworks on the internet is a recent phenomenon, one that comes with its own limitations. Texture as well as scale can be difficult to see, and the temptation to alter colors (hue, saturation, lightness,,etc.) is present and not always easy for the viewer to detect when it occurs. The chance to see all kinds of work that has been hard to find is also new, and that is exciting. These charming landscapes and still life paintings created a century ago by Koloman Moser were intended for the intimate spaces and domestic settings of Vienna are also....here...now.

These paintings are small (2.5 centimeters = I inch) but you can’t see the individual sizes or relative sizes of images on the internet. This is hardly a new problem; it is one that has bedeviled art book editors for decades. Museums with have greater latitude for making arrangements of artworks on display don't necessarily get it right either. And that is why I posed the question in the title of this post.

Viewing artworks on the internet is a recent phenomenon, one that comes with its own limitations. Texture as well as scale can be difficult to see, and the temptation to alter colors (hue, saturation, lightness,,etc.) is present and not always easy for the viewer to detect when it occurs. The chance to see all kinds of work that has been hard to find is also new, and that is exciting. These charming landscapes and still life paintings created a century ago by Koloman Moser were intended for the intimate spaces and domestic settings of Vienna are also....here...now.

Images:

1. Koloman Moser - Bergketten, 1913, Leopold Museum, Vienna. Size: 38 x 50.3 cm.

2. Koloman Moser - Marigolds, 1909, Leopold Museum, Vienna. Size: 50.3 x 50.2 cm.

3. Koloman Moser - Flowers And Ceramic Jug, 1912, Leopold Museum, Vienna. Size: 50.1 x 50.1 cm.

4. Koloman Moser - Wolfgangsee, 1913, Leopold Museum, Vienna. Size: 32.5 x 32.5 cm.

4. Koloman Moser - Wolfgangsee, 1913, Leopold Museum, Vienna. Size: 32.5 x 32.5 cm.