I. Perched on a hillside overlooking the village of Mezy-sur-Seine, this house looks like nothing so much as a luxury liner on the crest of a wave. And there is some poetic truth to this comparison. Villa Poiret is, arguably, the earliest example of what came to be known as ocean-liner chic during the inter-war years. Villa Poiret was also the first major design by architect Robert Mallet-Stevens.

Fashion designer Paul Poiret had wanted a suburban retreat for his family for several years when he commissioned the young Mallet-Stevens in 1921; he had approached other architects, including Le Corbusier but was dissatisfied with their plans. Yet Poiret was also in a hurry to have a house built. An avid yachtsman, he had purchased a property that would give him a front row seat for the boat races at the Summer Olympics scheduled for Paris in 1924.So eager, in fact, was Poiret that he moved into the grounds-keeper's cottage as soon as it was finished in 1923. He never did get to live in his landmark villa; there were delays in its elaborate construction, the House of Poiret went bankrupt in 1926, and the villa stood empty and deteriorating until Poiret sold it in 1930 to the Rumanian actress Elvira Popescu. It was Popescu who hired another architect, Paul Boyer, in 1932 to add the porthole windows. Popescu lived in the house until 1988, when it again became vacant and dilapidated; its current restoration began in 2008 and Villa Poiret is now recognized as a French national landmark.

Filmmaker Leos Carax knew this back story when he used Villa Poiret for a scene in his most recent film Holy Motors in 2012. A sophisticated and disorienting take on various film genres, Holy Motors takes the viewer on Surrealist Odyssey, his Odysseus is named Monsieur Oscar, the ship is a sleek white stretch limo captained by his equally sleek assistant Celine. Together they tour Paris on a series of mysterious engagements, each of which requires a different disguise for Monsieur, who uses the back seat as his dressing room. They travel mostly by night through half-lit landscapes that intimate ghostly events offstage. Carax, a Frenchman, was undoubtedly aware that Robert Mallet-Stevens was one of the first architects to take an interest in cinema; his set designs for the film L'Inhumaine (1924) are considered a masterpiece.

II. No one had a better biography for an architect than Robert Mallet-Stevens (1886-1945); you could make a movie out of it. He was born in Maison- Laffitte, a 17th centuryhouse designed by Francois Mansart, an architect admired for his elegance and subtlety, qualities that Mallet-Stevens absorbed into his own vocabulary. Mallet-Stevens was the son and grandson of art dealers and his mother was a niece of the Belgian painter Alfred Stevens. He was also the nephew of Suzanne Stevens, wife of the wealthy industrialist Adolphe Stoclet. Their home in Brussels, the Palais Stoclet built in 1905 on the Avenue Terneuven, was designed by Josef Hoffmann, architect of the Vienna Secession. Mallet-Stevens drew on Hoffman's design of Hoffmann's art colony Hohe Warte when he came to design his own, seven houses on rue Mallet-Stevens (1926-1938) in the 16th arrondissement of Paris.

Where Le Corbusier wanted to reinvent entire cities, Mallet-Stevens worked primarily on individual commissions, most of them in Paris, the city Le Corbusier would have razed if he had been given the chance. His ideas were less grandiose and he left behind no large theoretical work to buttress his reputation but Mallet-Stevens was not the light-weight that he has sometimes been portrayed to be; his excellent taste in collaborators set him apart from the self-promoting Le Corbusier. You could say that his death was ill-timed, taking place before the great post-war building boom. Nevertheless Mallet-Stevens was one of the two most influential French architects of the 20th century. Period photographs of his work are limited, partly because Mallet-Stevens asked that his archives be destroyed after his death.

III. “A little house, interesting to live in, to take advantage of the sun.”

That was how Mallet-Stevens modestly described his vision for his second important residence, designed for the Vicomte and Vicomtesse de Noialles. Soon after their marriage in 1923, the couple signed a contract with the architect to build them a summer home overlooking the Riviera. For this project Mallet-Stevens chose as his collaborators Elise Djo-Bouregois, Eileen Gray, Pierre Chareau, and Theo van Dosberg! What began as a simple country retreat became an “immobile ocean liner” with fifteen master bedrooms, swimming pool, squash court and a terrace for games of boules, retracting bay windows, clocks controlled by a central system, and a triangular-shaped 'Cubist' garden designed by Gabriel Guevrekian.

That was how Mallet-Stevens modestly described his vision for his second important residence, designed for the Vicomte and Vicomtesse de Noialles. Soon after their marriage in 1923, the couple signed a contract with the architect to build them a summer home overlooking the Riviera. For this project Mallet-Stevens chose as his collaborators Elise Djo-Bouregois, Eileen Gray, Pierre Chareau, and Theo van Dosberg! What began as a simple country retreat became an “immobile ocean liner” with fifteen master bedrooms, swimming pool, squash court and a terrace for games of boules, retracting bay windows, clocks controlled by a central system, and a triangular-shaped 'Cubist' garden designed by Gabriel Guevrekian.The clients, Charles and Marie-Laure, were wealthy art patrons with a taste for Surrealism; one of Marie-Laure's closest friends was Jean Cocteau. Her contemporaries found something of the surreal in the Vicomtesse herself: her family tree included Russian aristocrats, Quakers, and even the Marquis de Sade. Villa Noailles was featured in Man Ray's 1926 film Les Mysteres du Chateau de De, allowing a large public of moviegoers to glimpse a modernist masterpiece. What bankruptcy did to Villa Poiret, World War II brought to Villa Noialles. In 1940, the Italian army occupied the house, and forced its owners to leave. After the war ended, the Vicomtesse returned, living there until she died in 1970. The City of Hyeres purchased Villa Noailles in 1973, and it is now an arts center.

IV. At the same time that Mallet-Stevens was at work on Villa Noialles, he was invited by the French government to design theirembassy pavilion for the International Exposition of Decorative Arts Paris, 1925. His collaborators were Jan and Joel Martel, sculptor twins who designed the famous Cubist palm trees (Arbre Cubiste) for the garden in front of the pavilion. No stranger to world’s fairs, Mallet-Stevens had previously exhibited designs in Brussels, London, and San Francisco. After the fair ended, the concrete trees were destroyed; other than in photographs they survive in the form of a wooden model now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (In the photograph at left of the Martel brothers' studio, a maquette of the palm tree is visible in the alocve at right.) Among the most avant-garde works at the exposition, the concrete trees were were mocked in the press; in one cartoon a puzzled gardener tried to decide whether to water them.

Mallet-Stevens and the Martel brothers understood thatthe introduction of reinforced concrete changed everything; without it modern building is inconceivable “A thousand shapes are possible, unexpected silhouettes spring up, often strange, but rational and sincere. Reinforced concrete allows overhangs, the elimination of numerous points of support, and the reduction of the various structural elements to a minimum. So the proportions are profoundly modified and the aesthetic becomes different.” - Robert Mallet-Stevens in Architecture and Geometry (1924).

V. “The events of human life, be they public or private, are so intimately bound up with architecture, that the majority of observers can reconstruct nations or individuals in the full reality of their behavior, from the remnants of their public monuments or the examination of their domestic remains.” - Honore de Balzac, excerpt from The Pursuit of the Absolute (1832).

In the The Unknown Masterpiece, an otherwise ambiguous tale of the painter Francois Porbus, a man who is either a total failure or a misunderstood genius, Balzac based the artist's studio on a specific location, something he did over and over again. So vivid was Balzac’s word picture of the artist in his studio, down to its location in the rue des Grands-Augustins that Pablo Picasso took a studio there while he painted Guernica the 1930s. After reading The Unknown Masterpiece Picasso wrote, “Thanks to the never ending search for reality, [Balzac's artist] ends in black obscurity. There are so many realities that, in trying to encompass them all, one ends in darkness.”

After a fashion life for Robert Mallet-Stevens, a humane modernist, ended in darkness. For all that fortune had showered on him, he spent his final five years exiled in France's southern free zone in order to protect his wife Andree, who was Jewish. He died on February 5, 1945, six months before the liberation of his beloved city on August 25. Andre Mallet-Stevens survived him, living on until 1980. The Pompidou Center held a retrospective on the works of Robert Mallet-Stevens in 2005.

Visit the always fascinating Cinetourist for more about Holy Motors.

Note: This piece is dedicated to Tania who drives down Avenue Terneuevn past the Palais Stoclet every day.

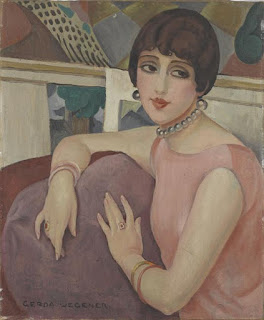

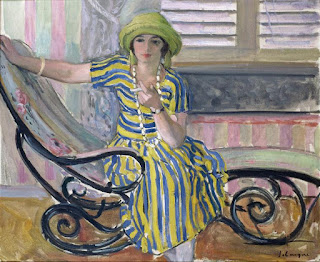

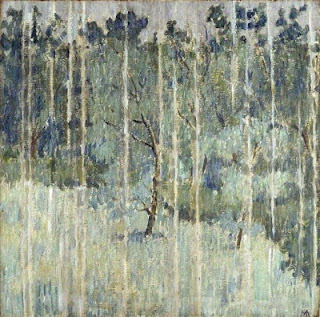

Images:

1. Caroline Champetier - cinematographer - Holy Motors, 2012, Les Films du Losange, Paris. c.1926-30, Grand Palais, RMN, Paris.

2. Anna Blair - Exterior view of vaill martel on rue Mallet-Stevens, Paris, from Anna Blair: Untapped Paris.

3. Jacquleine Salmon - Villa Noailles, no date given, Pompidou Center, Paris.

Unidentified photographer, Marie-Laure & Charles de Noailles,

4. Therese Bonney - Studio at Villa Martel on rue Mallet-Setevens, Paris, Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum, NYC.

5. Therese Bonney - Terrace of Villa Mallet-Stevens, - home of the architect in Paris, 192, Pompidou Center, Paris.

7. Louis Marcoussis - Robert Mallet-Stevens, 1932, Villa Cavrois, Roubaix.